Modigliani Sculptures: Caryatids, Stone Heads and the Origins of his Style

Amedeo Modigliani remains most famous for his Modernist portraits, featuring elongated faces and blanked out eyes. Prior to that series of work came his sculptures, which ultimately provided the stylistic driver to all that followed.

The artist devoted himself entirely to sculpture between the years of 1909 to 1914 and was able to produce a highly influential body of work in this period. Without this part of his career, his most famous paintings would never have come about. In this page we will examine the different types of Modigliani sculptures, including his stone heads and caryatids, as well as trying to understand what lay behind his unusual sculpting style. Other parts of his career are covered in our biography.

In order to truly understand Modigliani, one must absorb his paintings, sculptures and drawings, and see how they fused together into a single output of work. His unique portrait style came about from the discoveries that he made in a short period of sculpture, as demonstrated below.

- Artist: Amedeo Modigliani

- Period: c. 1909-1914

- Medium: Limestone, Sandstone

- Key Forms: Stone heads, Caryatids

- Influences: African masks, Cycladic and Egyptian art

- Significance: Foundation of Modigliani's painted style

Why Modigliani Turned to Sculpture (1909-1914)

Amedeo Modigliani found a home in Paris, amongst like-minded creatives at the start of the 20th century. It was a truly avant-garde scene, covering a mixture of artistic mediums - perfectly suited to the curious mind of this independent Italian. Traditionally, Paris had followed the academic path, with approved methods of study and technique, but this had changed from around the mid-19th century.

He would make friends with a number of artists in Paris at the time, some of whom would go onto become household names. This brought him into contact with new ideas, some of which he would incorporate into his own work. Constantin Brâncuși invited him into his studio and it was here that he witnessed the carving techniques which immediately appealed.

The Italian liked the idea of reducing form down to its simplest components and sculpture proved the best format for this. He also wanted to move away from replicating reality, and he could now study more abstract styles of sculpture from alternative cultures. He realised that he could potentially create a new sculptural style that fused different influences together. The spirit in Paris at the time was very much about experimentation and innovation, and perhaps this rubbed off on the young Amedeo.

As with would later turn out, and totally unplanned, his sculptures would influence his paintings in later years - where elongated faces, blanked out eyes would cross over into his oil works, as well as his study sketches. He would later become respected for his contributions to all three mediums, which is a rare achievement.

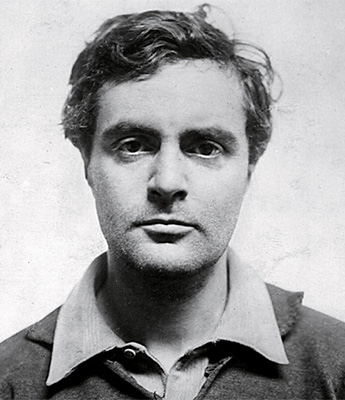

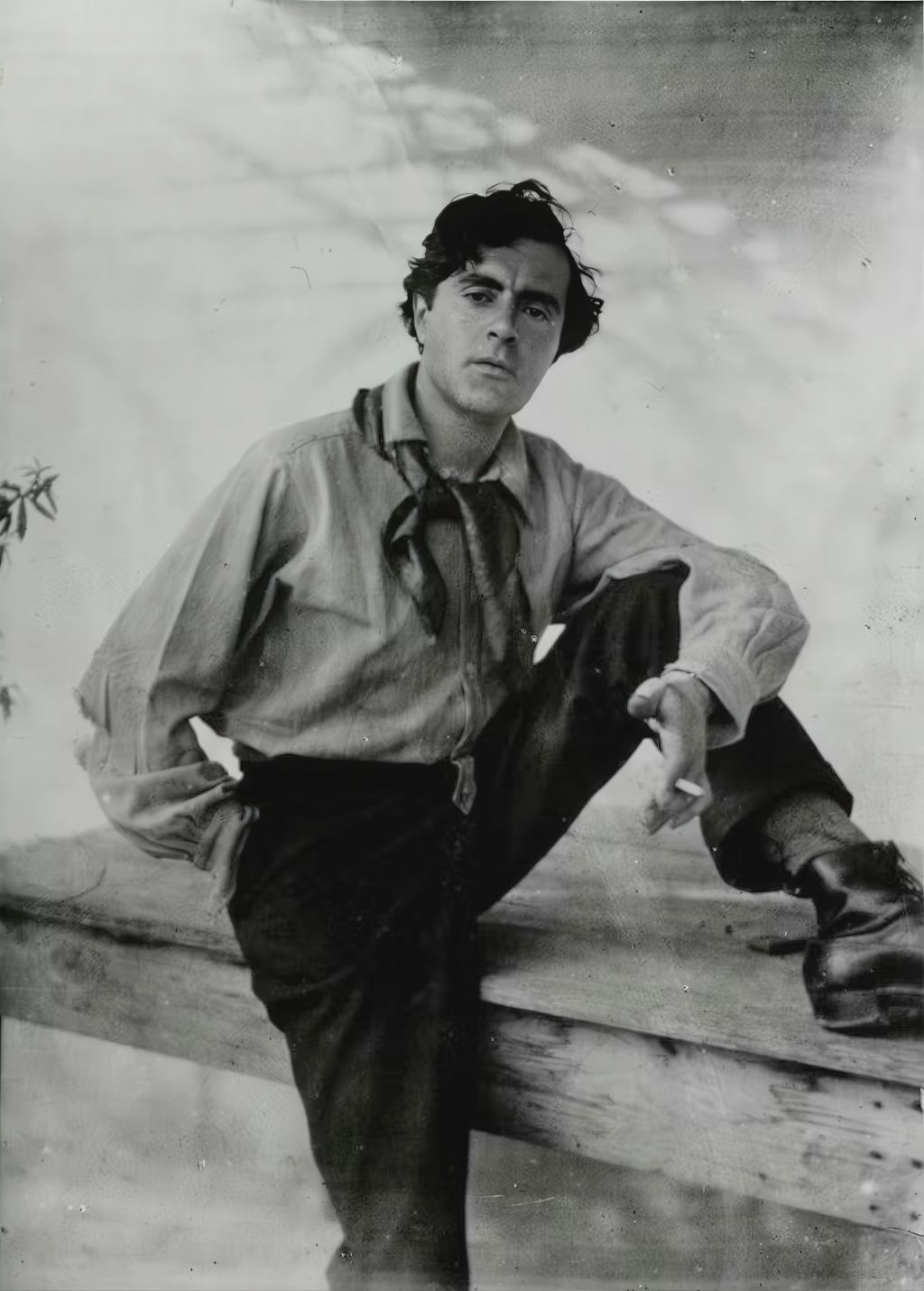

Amedeo Modigliani (by an unknown photographer)

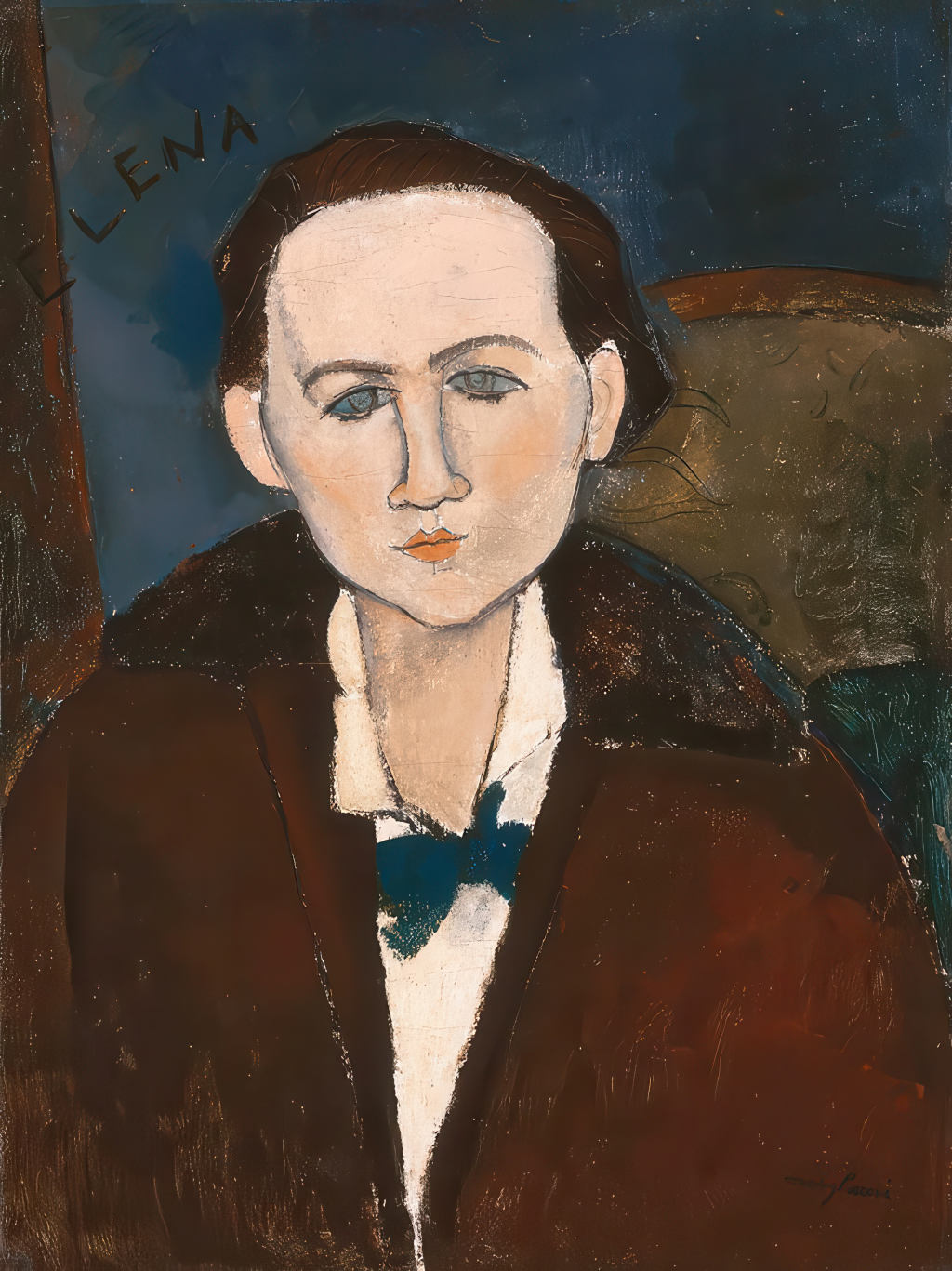

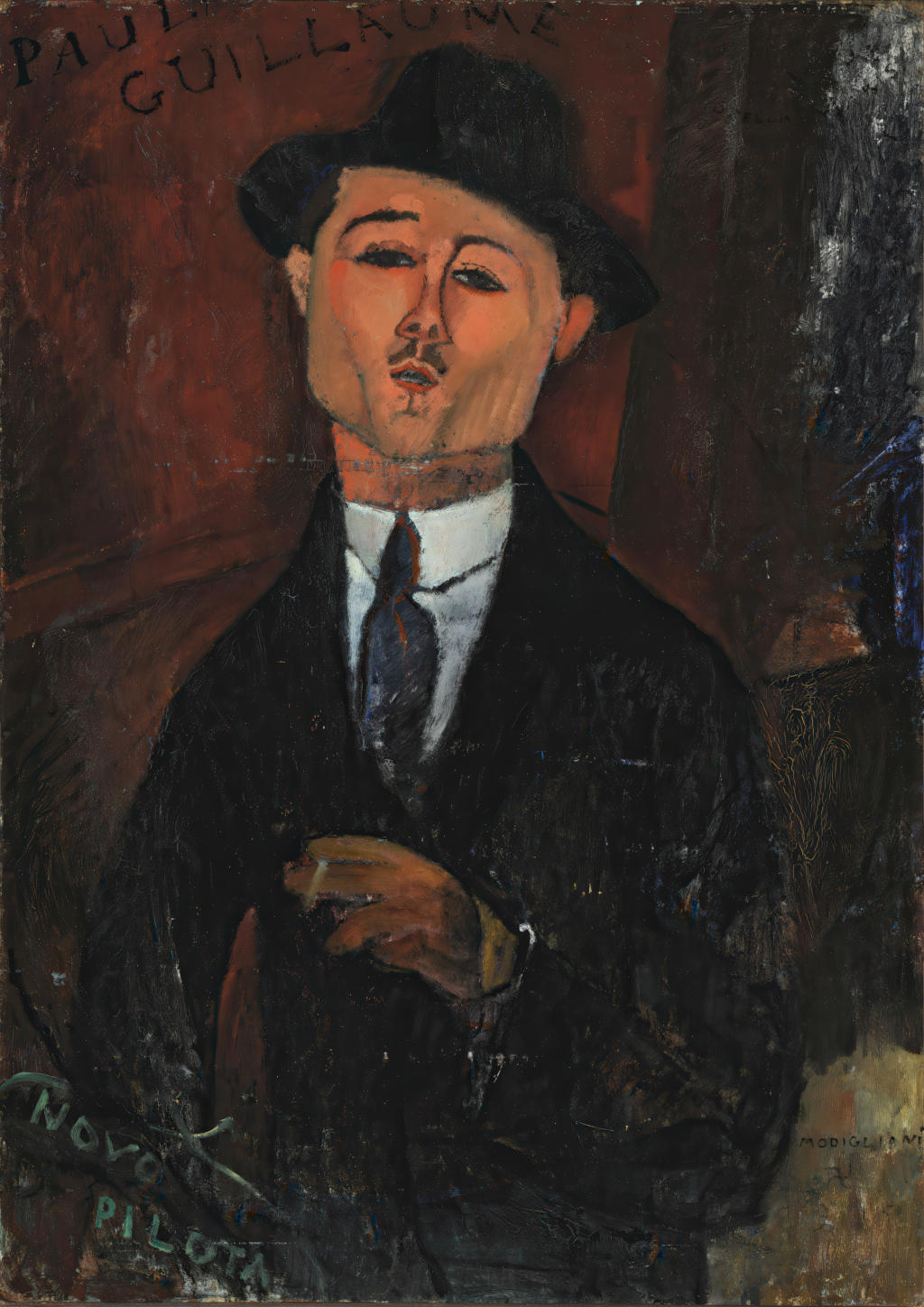

Four sculptures by Modigliani exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne along with the Cubists

Modigliani's Stone Heads

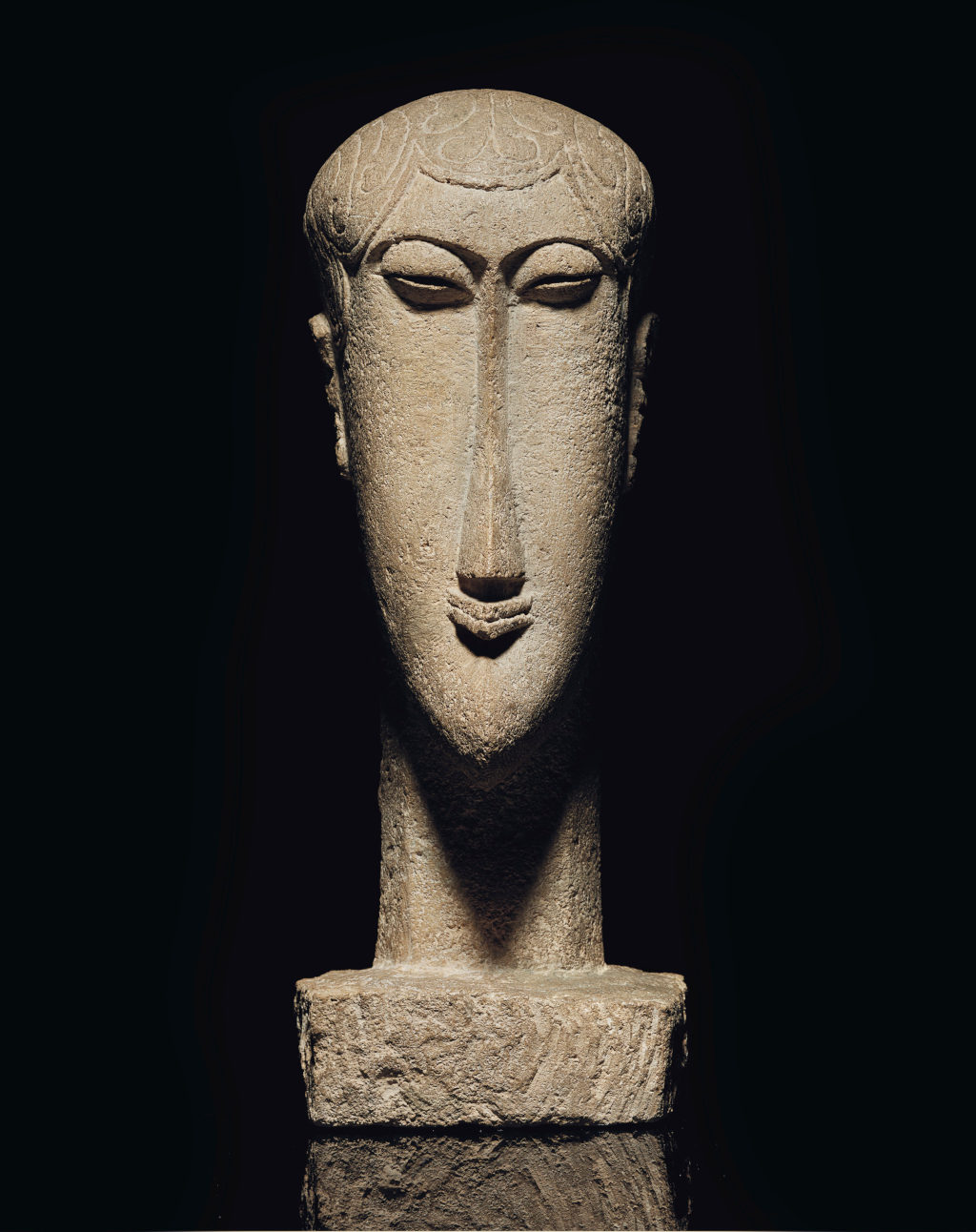

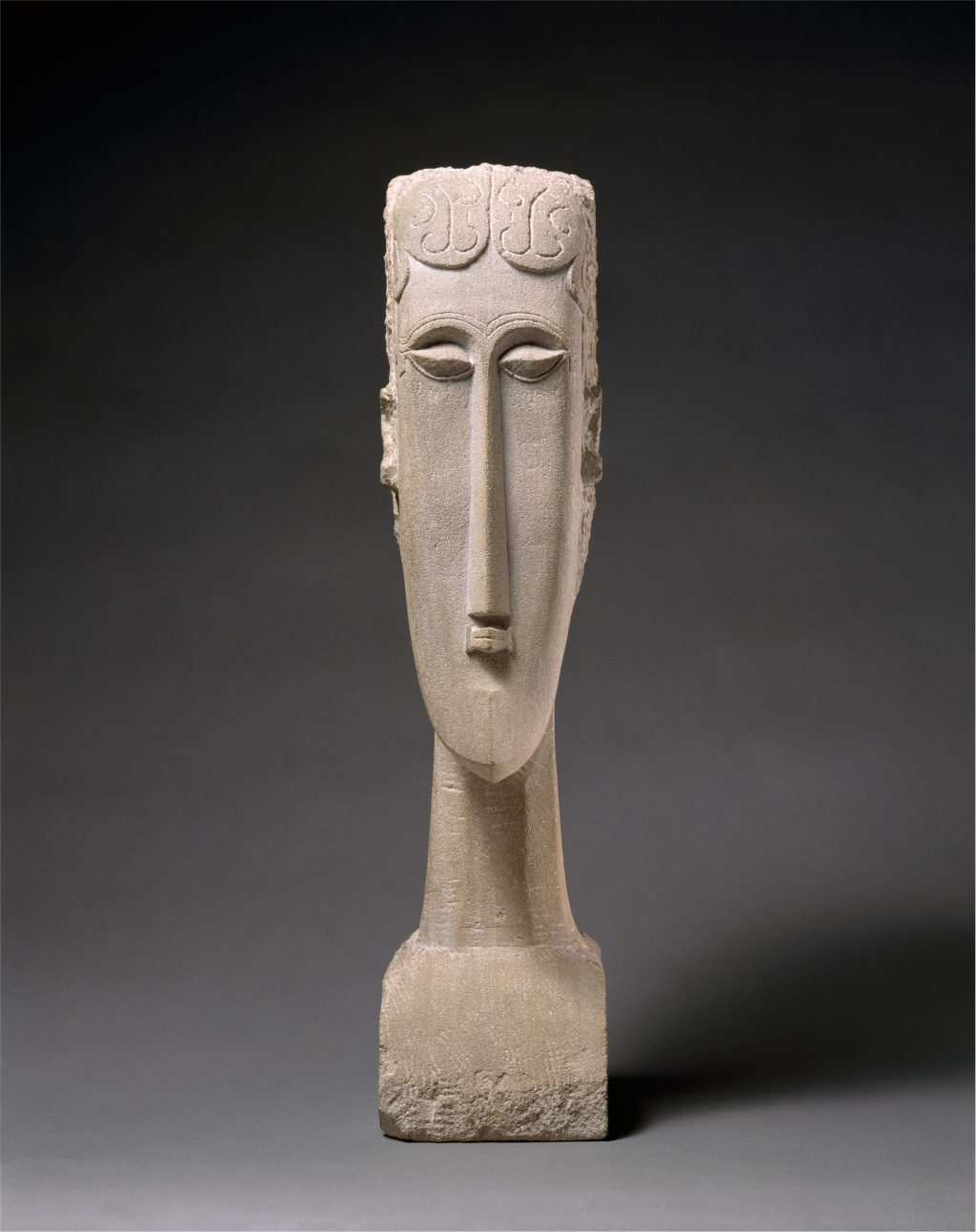

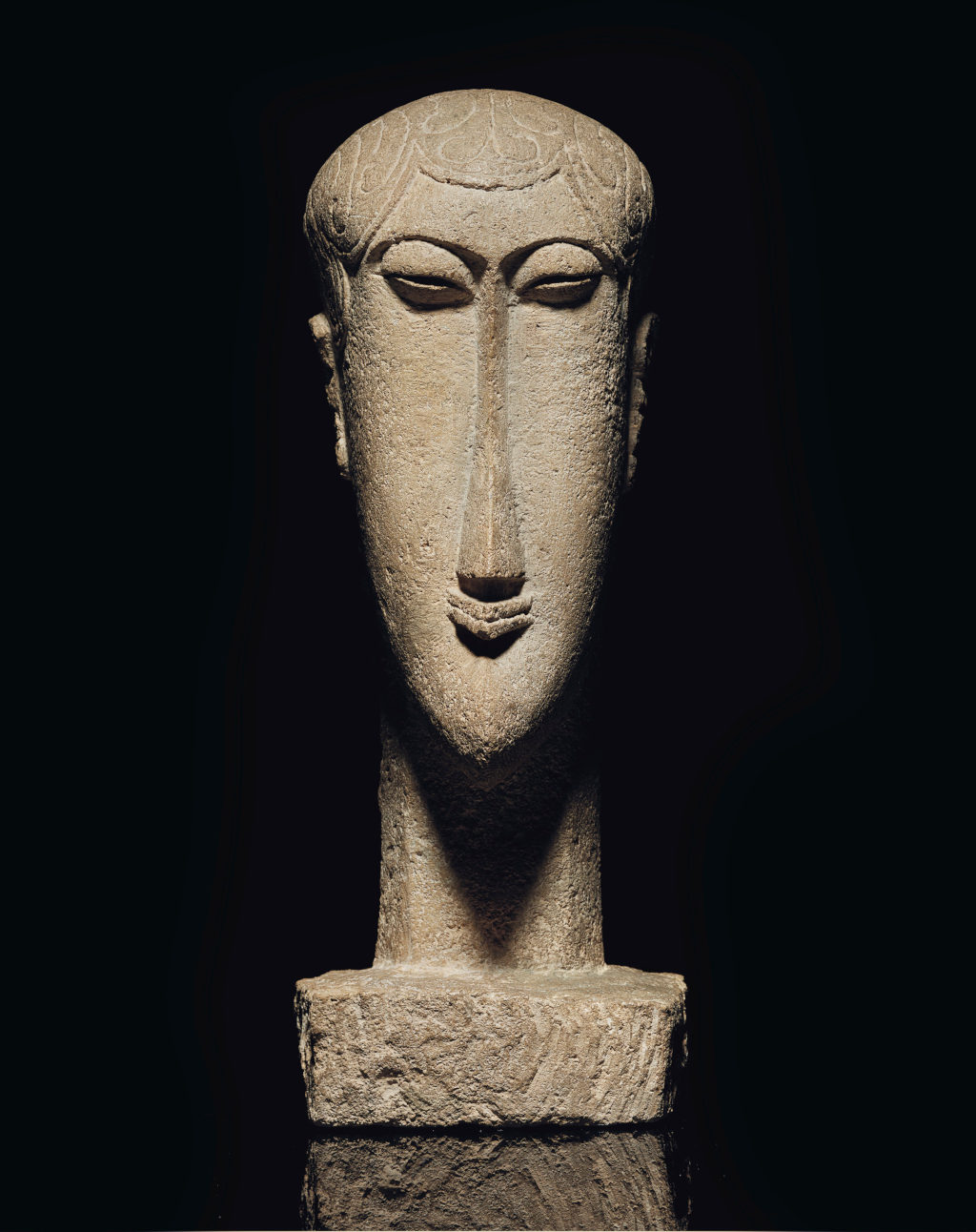

Modigliani's stone heads are immediately recognisable and represent the artist's most famous contribution to this artistic discipline. He typically carved in limestone or sandstone, and his creations featured Elongated oval faces, long, straight noses, narrow, closed mouths and almond-shaped or hollowed-out eyes.

Even the most fleeting art history follower would understand their influences from African and Oceanic sculpture from a simple glimpse at these pieces. Additionally, Modigliani would make use of calm expressions, with relatively little emotion in his sculptures, with the head looking directly forward.

One felt relaxed in their presence, and they also were designed with symmetry in mind, where even the elongated elements would fit together in the artist's own use of proportion. It did not feel like early 20th-century Paris, nor was it intended to.

Despite being new to sculpture at the time, Modigliani avoided any temptation to try out wild postures, multiple mediums or different styles of portrait - he settled on a particular look and remained consistent throughout his stone head series. Even when moving away from sculpture as his health deteriorated, he would simply translate elements of this approach into his paintings, developing a look which spread seamlessly across different disciplines.

Modigliani carved directly into stone, leaving visible tool marks that contrast with smoother planes of the face. This balance between rough and smooth surfaces enhanced the sculptures' aesthetic. Unlike academic sculptors, he avoided excessive polish, allowing the stone's weight and texture to remain, possibly in part due to his own health issues where energy levels could run low from these arduous carving techniques.

Woman's Head. Amedeo Modigliani, 1912, Limestone (Source: The Metropolitan Museum)

Elongated Face, Detail of Woman's Head. Amedeo Modigliani (Source: The Metropolitan Museum)

Caryatids: Modigliani's Obsession with the Human Figure

What is a Caryatid?

A caryatid is a sculpted female figure used as an architectural support, replacing a column or pillar. Caryatids typically bear the weight of an entablature (upper part of a classical building) on their heads and are characterised by upright posture, elongated bodies and draped clothing which echo the structure of classical columns.

The most famous caryatids appear on the Erechtheion on the Acropolis in Athens (5th century BCE), where six stone maidens support the roof. Since antiquity, caryatids have symbolised strength, balance and the fusion of the human and architectural structure.

In modern art, artists such as Amedeo Modigliani reinterpreted the caryatid as a timeless, symbolic figure rather than a literal architectural support, using it to explore form, monumentality and the human body as structure - he did so both in sculpture and also study drawings.

Modigliani's Obsession with Caryatids

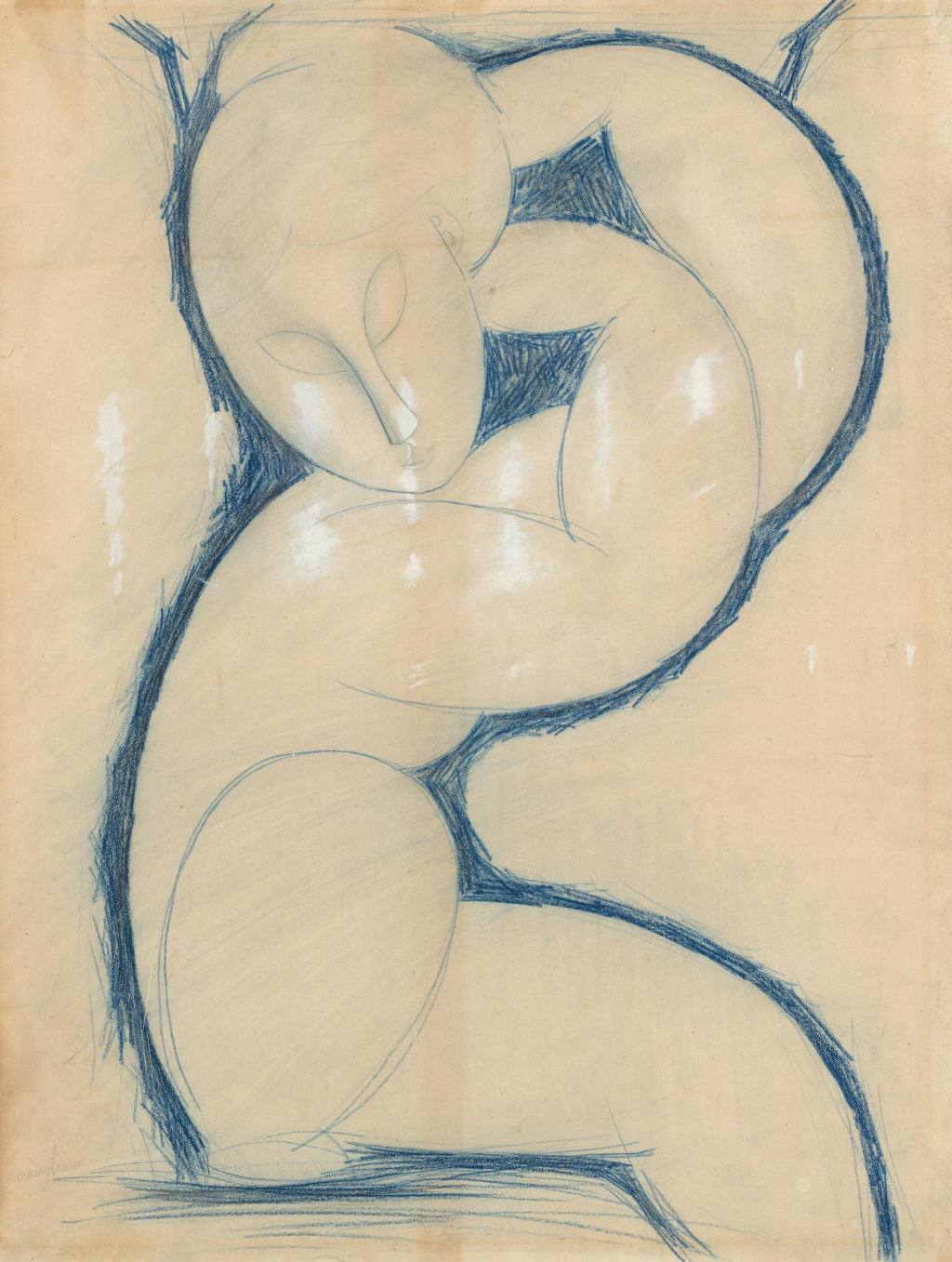

Modigliani devoted a considerable amount of time in studying and perfecting his work with caryatids. It served as another example of his wide range of sculptural influence, from different periods and regions of the world. There would be hundreds of study drawings in his career, and from them came a few sculptures in which he explored his ideas in the third dimension.

These offer a different look to his stone heads, and together they are the two pillars of Modigliani's sculptural output. As with his stone heads, his caryatids feature elongated features, though the postures are far more interesting and varied, more figurative than busts. The nature of this format meant that contorted bodies would work against an invisible structure above.

The artist explored more variations within his drawings, and would save his energy for the hard work of sculpture for short periods. This became more and more the case as his health continued to worsen. His completed sculptures simplified many of the elements that he experimented with in his drawn studies, such as posture, muscular balance, and overall composition.

Caryatid by Amedeo Modigliani, c. 1914, limestone, Museum of Modern Art

Modigliani's Preparatory Caryatid Drawings

Modigliani's studies for caryatid sculptures were serious and comprehensive. He aimed to produce a Temple of Beauty, ultimately, though this never materialised. He was limited in his output with sculpture because of his health problems, and so he wanted to investigate as much as possible in his preparation stages.

In terms of technique and medium, most of his caryatid drawings were in pencil, charcoal, ink, and crayon, sometimes as a combination. He would use an economy of line, in order to ensure a smooth flow, but would place more attention on muscular balance, slowly building up contours. All the while that he was doing this, he would be imagining the potential sculptural, its textures, angles and third dimension.

Modigliani considered drawing to be an extension of sculpture, and not of painting. We can make this assumption based on how he built up his sketches, where he would take on a subject from different angles and experiment with subtle changes to proportion. Amedeo would fight a constant battle between remaining spontaneous in his work, whilst also ensuring some level of discipline in order to aid his learning.

Modigliani's Preparatory Caryatid Drawings

Featured Modigliani Sculptures

Head

Head of a Woman

Tête

African and Archaic Influence on Modigliani's Sculpture

Modigliani was able to study a large number of artifacts in Paris in order to develop his knowledge of many different cultures. Items of African and archaic art, including sculptures and masks were present in the collections of several friends and contacts in the art world, alongside several public museums.

One can immediately see the connection between African masks (especially Fang and Baoulé), with their elongated faces and simplified features, and Amedeo's work in sculpture. He would also extract the smooth planes and reduced anatomy from Cycladic sculpture. Additionally, Ancient Egyptian art possessed frontal poses, long necks and serene expressions which he also made sketches of.

The artist would slowly fuse these different styles together, somehow managing to forge a new sculptural style which offered something unique within early 20th century Paris. His oeuvre would become another sphere of the movement away from imitation towards expressive art.

From Stone to Canvas: How Sculpture Shaped Modigliani's Paintings

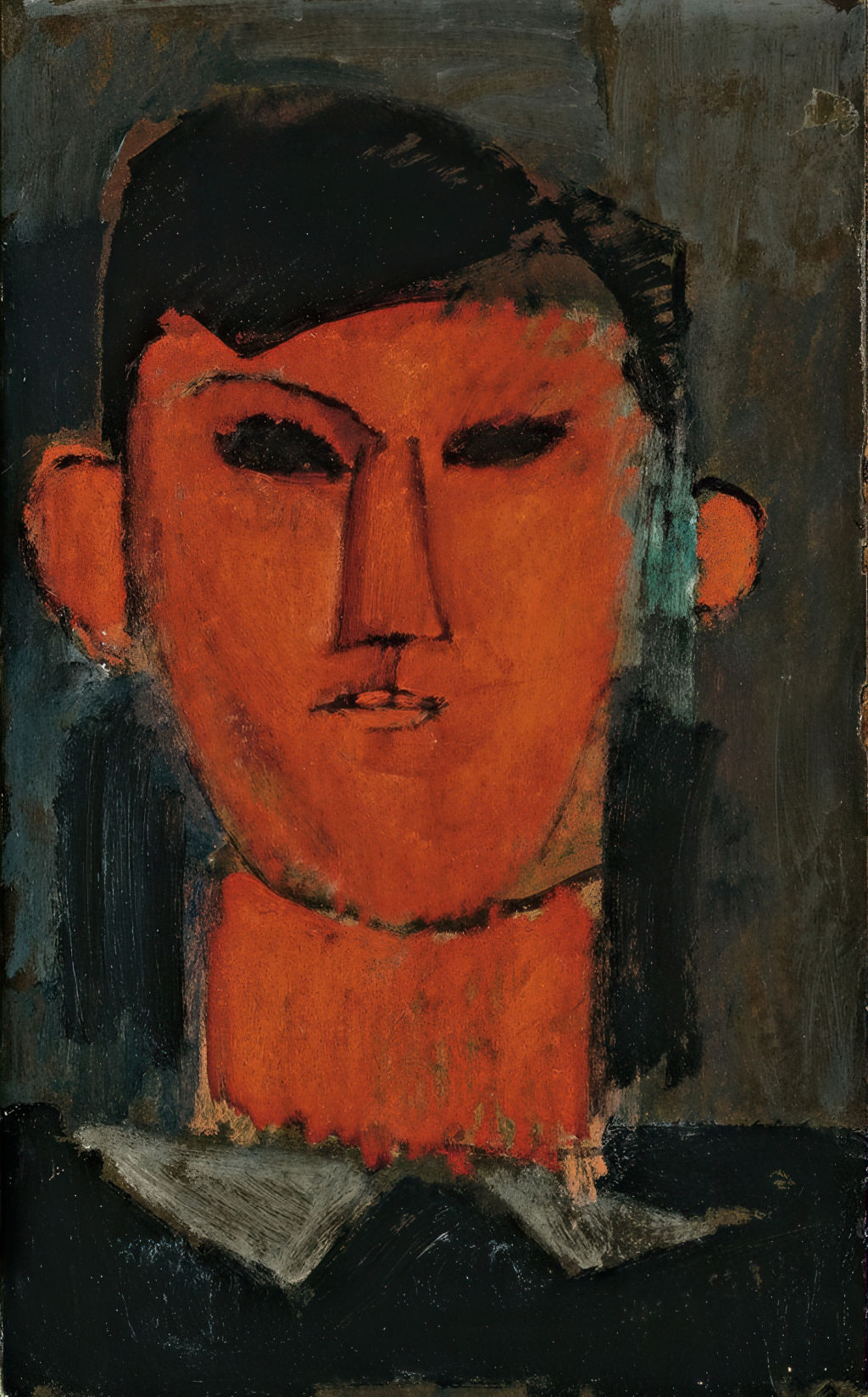

After switching from sculpture to painting, Modigliani still often thought first as a sculptor. One can see from his portraits to reclining nudes, featuring smooth lines, elongated faces and blank eyes that the elements of his stone heads, in particular, was still present. Colour is not a major factor in his paintings for this very reason - he was used to working with single tones of stone.

Why Modigliani Abandoned Sculpture

Sadly, Amedeo Modigliani was forced to abandon his use of sculpture in around 1914. His health was worsening, and the intensive working practices involved with carving stone would start to take its toll.

With the outbreak of WWI there was also considerable disruption in his life, including the ability to even source the required materials for his work. Painting was a more established medium within Paris, and so it was an easier option at that time, as was drawing. His sculpture output was essentially frozen in time as his tuberculosis continued to take hold, though today this has helped increase the significance and monetary value of each piece as a result.

In some cases, these setbacks can bring new opportunities - we are all aware of Monet's sight issues which impacted his palette, whilst Matisse experimented successfully with cut-outs once he became bed-bound in later life.

The Legacy of Modigliani's Sculpture

Today, we recognise Modigliani's sculptures as a significant part of his artistic development, and far more than a short-lived side-interest. They help us to understand the signature elements of his work, across all mediums, such as his elongated faces and necks, as well as his blanked-out eyes. He was an artist searching to simplify form, and would eventually take his ideas over into painting and drawing.

His influences from non-European sculpture and masks brought a uniqueness to his work within Paris at the time and sat confidently alongside Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism. It took time for the critics and public to catch up, but today his sculptures enjoy a central role in Modigliani's artistic story.